A comparatively minor bureaucratic change proposed by the Federal Housing Finance Company stirred up a viral storm in right-leaning information media not too long ago, with retailers just like the Washington Times, New York Post, National Review and Fox News all reporting some variant of the sentiment expressed within the Occasions headline: “Biden to hike funds for good-credit homebuyers to subsidize high-risk mortgages.”

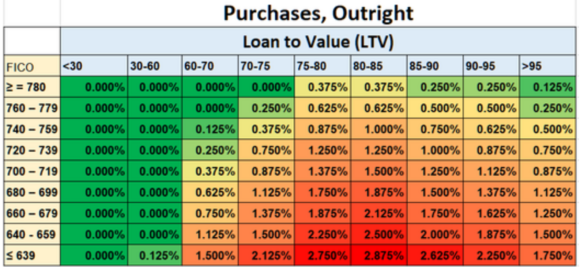

The underlying challenge issues the FHFA’s current determination—as conservator of the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs)—to revise the loan-level worth changes (LLPAs) charged by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which collectively account for roughly 60% of U.S. residential mortgage loans. The LLPAs that the GSEs cost are decided primarily by mortgage sort, loan-to-value ratio and a borrower’s credit score rating.

What’s broadly true within the protection is that the modifications—which have been first announced in January, have an effect on loans delivered to the GSEs on or after Could 1 and due to this fact have already been applied by lenders for months—do on stability have a tendency to scale back prices for these with decrease credit score scores and enhance prices for these with greater credit score scores. In actual fact, as a part of a broader repricing change introduced final 12 months, the FHFA eradicated charges altogether for standard loans for about 20% of residence patrons, financed by increased upfront fees for second houses, high-balance loans, and cash-out refinancings.

Sadly, the way in which this story has been spun within the wake of the modifications would go away many information shoppers with the impression that debtors with greater credit score scores will likely be paying extra outright in charges than debtors with decrease credit score scores. That is definitely not the case. Evaluating apples to apples, at each stage of the grid, a borrower with the next credit score rating would proceed to have decrease LLPAs (or, in lots of LTV classes, none).

Writing in his Substack newsletter Kevin Erdmann of the Mercatus Middle responded to a Fox Information graphic that declared, beneath the brand new guidelines, a “620 FICO rating will get a 1.75% price low cost” whereas a “740 FICO rating pays a 1% price”:

I’m fairly certain what they’ve achieved right here is cherry choose the low credit score rating that had the most important price lower. Then, they reported the full price of a better credit score rating. So, a low down cost 620 rating has a price that went from about 6.75% to five% (when mortgage insurance coverage is included). And, additionally, the price for a 740 rating went from 0.25% to 1%. (plus a 0.25% mortgage insurance coverage price). Why didn’t they only say that charges for 740 scores went up 0.75%? It will nonetheless get their partisan level throughout. It will nonetheless be bizarre, as a result of it could be describing mortgages with two completely different down funds. And it could disguise the truth that the 620 rating nonetheless has a price that’s greater than 3% greater than the 740 rating. However, a minimum of it wouldn’t be mixing ranges with modifications.

In the end, whether or not these explicit modifications are good or unhealthy for the GSEs is an actuarial query. As Erdmann goes on to notice, there are good causes to consider that the charges on lower-credit debtors have been too excessive for an prolonged interval.

However there are different causes to be involved about what the incident may imply for insurance coverage markets. Right here, the fear is that state regulators—or, within the worst-case situation, Congress—would possibly suppose charging these with excessive credit score scores extra to subsidize these with low credit score scores would possibly really be an concept worthy of emulation.

Clearly, insurers’ use of credit score data in underwriting and rate-setting has been a topic of public debate for happening 4 a long time. At this level, whereas a handful of states prohibit the observe outright, most have adopted laws that allows it, with some caveats.

The FHFA precedent—permitted as a result of Fannie and Freddie have been within the company’s conservatorship for shut to fifteen years—is especially regarding given current instances of state insurance coverage regulators transferring to restrict or ban the usage of credit score data with none express path from state legislators to take action. Whether or not courts select to uphold such unilateral selections depends upon the particularities of state legislation.

Final 12 months, Washington State Insurance coverage Commissioner Mike Kreidler moved to undertake a everlasting rule enacting a three-year ban on the usage of credit-based insurance coverage scores, after a predecessor emergency rule to do the identical was declared invalid in September 2021 by Thurston County Superior Courtroom Decide Indu Thomas. An August 2022 final order from Thomas discovered that Kreidler exceeded his authority in adopting the rule when there was a selected state statute that allowed insurers to make use of credit score scoring.

Extra not too long ago, the Nevada Supreme Courtroom ruled in February to uphold a short lived ban on the use credit score data in insurance coverage rate-setting initially issued by the Nevada Division of Insurance coverage in December 2020. The rule, which is scheduled to run out Could 20, 2024, was unsuccessfully challenged by the Nationwide Affiliation of Mutual Insurance coverage Firms.

The rise of credit-based insurance coverage scoring has revolutionized the trade, permitting vastly higher segmentation and higher matching of danger to fee. The place state residual auto insurance coverage entities as soon as insured as a lot as half or extra of all private-passenger auto dangers, they now signify lower than 1% of the market nationwide. It will be unlucky if some deceptive headlines impressed ill-considered regulation to reverse that progress.

An important insurance coverage information,in your inbox each enterprise day.

Get the insurance coverage trade’s trusted e-newsletter